For 127 years, trains rumbled through downtown Kalispell, Montana.

The Great Northern Railway’s transcontinental rail line to the Pacific Northwest arrived in the dusty frontier town on January 2, 1892, and with it came prosperity that would fuel the community’s growth for decades.

Trains passing the Kalispell Depot in the early 1900s and early 2000s.

“The citizens are justly enthusiastic over the advent of the Great Northern Railway. Bands played upon the streets all afternoon and tonight it is ablaze with colored lights. This is the ‘red letter’ day for the metropolis of the Flathead Valley, one to be remembered by everyone who witnessed it”

Salt Lake Tribune, January 2, 1892

Railroads were the broadband internet of the 19th century. When a railroad arrived in a small town, that community was suddenly connected to a network that could bring people and goods that would fuel economic and cultural prosperity.

In the late 1880s, one of the greatest railroad builders ever known, James J. Hill, was extending his iron road west across North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Washington and towns like Kalispell waited with bated breath wondering if they would become the next station stop.

From 1892 until 1904, Kalispell was a division point on the Great Northern’s main line to the Pacific Northwest. Located in the heart of Montana’s Flathead Valley, Kalispell was just north of Flathead Lake — the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River — and the economic heart of the region. But within a few years of arriving in the Flathead Valley, the Great Northern grew tired of the challenges of running trains over Haskell Pass, a steep mountain grade west of Kalispell.

In 1904, the Great Northern rerouted its main line in the Flathead Valley to go through Whitefish, about 15 miles north of Kalispell. The decision to reroute the line was controversial for locals because initially the railroad lied and said they were only seeking a route north into the coalfields of British Columbia and Alberta. But eventually the truth came out. The route between Kalispell and Libby (where the new route met back up with the old route) was no longer needed and abandoned. The 15 miles from Columbia Falls (where the new main line headed west to Whitefish) and Kalispell became a lightly-used branch line.

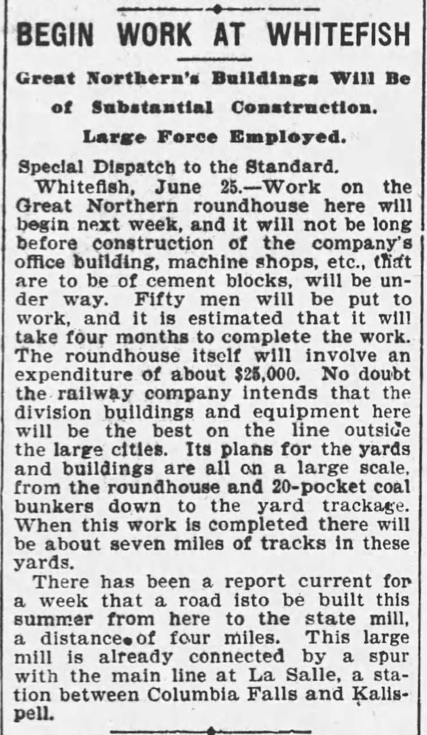

In June 1904, the Great Northern’s expansion in Whitefish was big news, as noted in this clipping from the Anaconda Standard.

According to newspaper accounts of the era, a “great gloom” descended on Kalispell as townspeople worried about their community’s future.

Despite losing the main line to Whitefish, Kalispell did not shrivel up and die like other less fortunate communities. The city continued to prosper and remained the economic heart of the Flathead Valley, dominated through much of the 20th century by logging and agriculture. But that began to change in the early 2000s, as tourism began to emerge as the dominate industry in the region.

By the 21st Century, the railroad yard near downtown Kalispell had become an eyesore to local leaders who proposed replacing it with a walking trail that they hoped would spark commercial and residential development more in alignment with the region’s tourism focus.

In 2015, the city received a $10 million federal grant to help build a new rail-served industrial park east of Kalispell. The rail park would allow the two remaining freight customers in Kalispell — a grain elevator and a drywall distributor — to move into a new facility outside the confines of downtown.

In 2018, I began documenting the final days of the railroad through downtown Kalispell, initially for the weekly newspaper I worked for, the Flathead Beacon, but later myself. I spent a day with the train crew that brings freight cars down from the main line in Columbia Falls. I spent a cold morning with the guys who unload flatcars of drywall. I climbed all over the grain elevator as they loaded grain and wheat into freight cars bound for distant markets. And I watched as city leaders and community members came together to plan how they would rebuild the heart of their city…

The Railroad

Scenes along the Mission Mountain Railroad between 2011 and 2019

A century after the line to Kalispell was turned into a branch line, the Great Northern’s successor, BNSF Railway, decided to lease the line to a company that specializes in operating secondary railway lines. In 2005, Watco Companies established the Mission Mountain Railroad to operate two different branch lines in Northwest Montana: one between Columbia Falls and Kalispell and another between Eureka and Stryker.

In March 2018, I spent the day with the crew of the Mission Mountain’s Kalispell Local. After organizing their paperwork at the small office in Columbia Falls, the Mission Mountain crew picked up their train and headed south. Along the way, they would stop at a lumber mill and scrap dealer in Evergreen to pick up and drop off freight cars. Finally, they arrived in downtown Kalispell where they would drop off cars of drywall and pick up loads of grain.

The crew of Mission Mountain’s Kalispell Local — Conductor Jason Sharp, Brakeman Reed Edwards and Engineer Brent Keys — go about their day on March 28, 2018.

The Shippers

Scenes at the CHS Kalispell grain elevator in the spring of 2018.

When the Great Northern Railway first arrived in Kalispell, industries quickly sprung up around the rail head. To serve all the industries, the railroad built a large yard not far from main street so that it could move freight cars around.

However, as the nature of the Flathead Valley’s economy changed, so did the industrial character of downtown Kalispell. In the early 1980s, a large portion of the rail yard was ripped up and replaced with a large shopping mall and parking lot along U.S. Highway 93. The rail line was routed around the mall so that it could reach the final two businesses that used the railroad: the grain elevator and a drywall supplier.

The concrete silos of the Kalispell Flour Mill Co. were erected on the corner of Railroad Street and Sixth Avenue in 1909 to replace a smaller facility that had been built a decade or so earlier. The Kalispell Flour Mill changed hands and eventually became CHS Kalispell in 1997 following the merger of two local cooperatives.

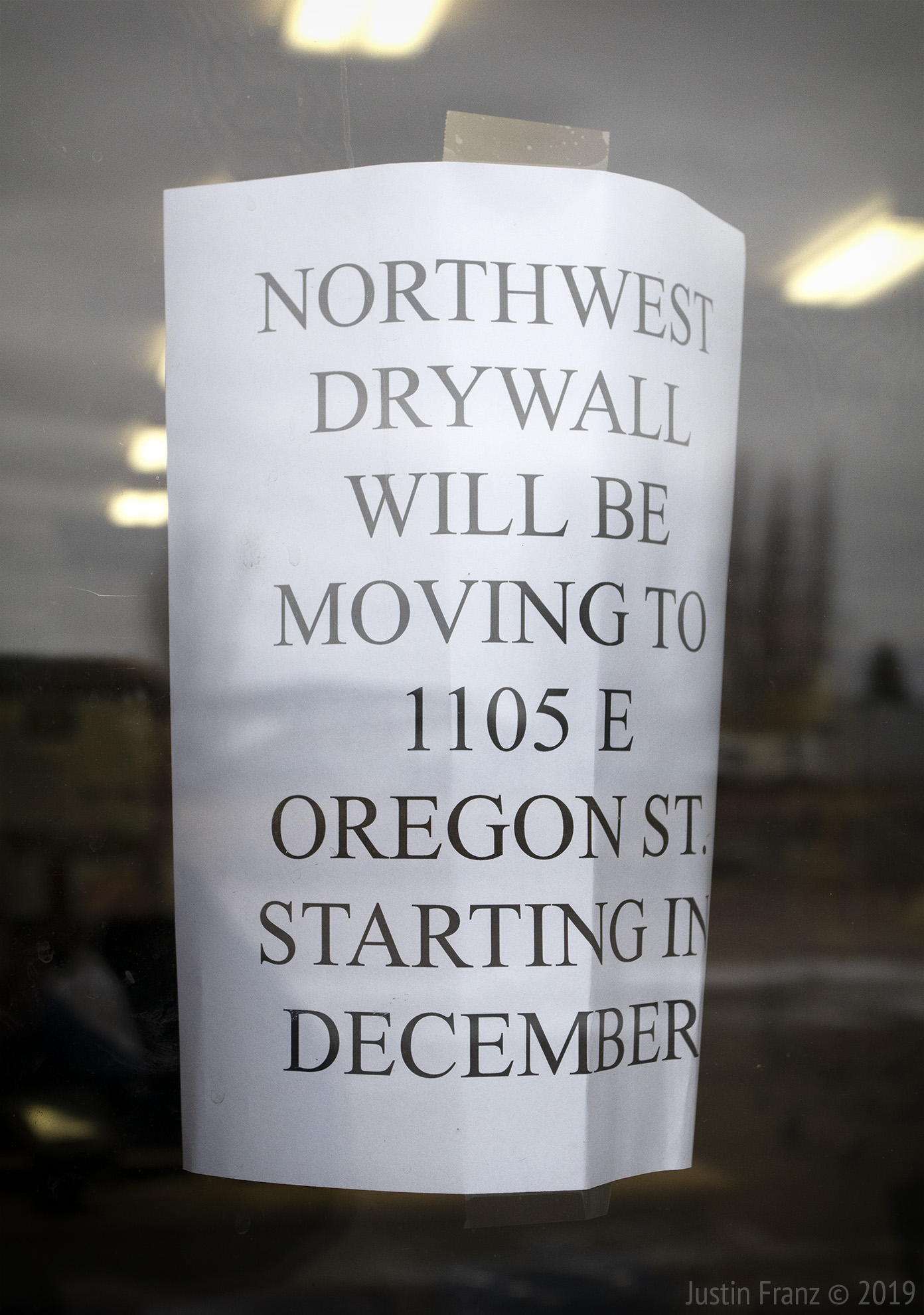

The other shipper, Northwest Drywall, was founded in 1988 and had a warehouse on Eighth Avenue. Every few days or weeks, Northwest Drywall received boxcars or bulkhead flatcars loaded with drywall and other construction materials.

Kent Loveall and Jon Greiting unload a car of drywall that came from Wyoming on April 3, 2018.

The Future

For decades, city leaders dreamed of redeveloping Kalispell’s under-used industrial core. That dream got a major boost in 2015, when the City of Kalispell won a $10 million federal grant to help build a new rail served industrial park east of town. The industrial park would allow CHS Kalispell and Northwest Drywall to move out of their downtown locations and for 2 miles of track through town to be abandoned and replaced with a walking path.

In 2017, work began on the new Glacier Rail Park on the edge of town. Basic infrastructure was completed in 2018 and a grand opening ceremony was held later that year.

Meanwhile, officials began to look at how they could redevelop the core area of downtown and build a rail trail. In the summer of 2018, a design group arrived and held town hall meetings to ask the community what they wanted the development to look like. They also give city officials and local residents rides on the 2 miles of track that would eventually be ripped up to give them an idea of what was possible.

The Final Trains

In 2019, CHS Kalispell and Northwest Drywall continued construction on their new facilities at the Glacier Rail Park. Knowing the final days were nearing for the railroad through downtown Kalispell, I redoubled my efforts to photograph it. Whenever the train passed my downtown office, I would sneak away to grab a few photos.

That spring, an old caboose was transformed into a private cabin in Columbia Falls on the Mission Mountain’s property. Once the car had been repainted, the railroad’s general manager, Kyle Jeschke, invited to the owners to take a ride to Kalispell before the caboose was trucked to its new home. The “caboose hop” would be the last train to take passengers to Kalispell.

The Mission Mountain Railroad in 2019

In the early Fall, CHS Kalispell opened its facility out at the Glacier Rail Park and stopped loading freight cars downtown. Construction of the new Northwest Drywall facility, however, was delayed and it would not be ready until December. On Dec. 13, the last carload of freight arrived downtown and it was unloaded a few days later.

The Flathead Beacon, December 18, 2019

“When the railroad came to Kalispell in 1892, it was the beginning of a new era. Now, as the railroad leaves 128 years later, another era is set to begin.“

Kalispell City Planner Tom Jentz

On December 27, 2019, just four days shy of the 128th anniversary of the Great Northern Railway’s arrival, the Mission Mountain Railroad ran its last freight train out of downtown Kalispell. While the last carload of freight had been delivered a week earlier, there were still some unused freight cars stored at the end of the tracks.

Before hooking up to the stored freight cars near Meridian Road, the crew parked the locomotive — painted blue and white in honor of the Columbia Falls Wildcats — in front of the old CHS grain elevator for a few photos with Montana West Economic Development, the organization that helped spearhead the construction of the rail park.

As dusk drew near, the Mission Mountain locomotive coupled up to the stored freight cars and slowly rolled past the grain elevator, behind the mall and over U.S. Highway 93 one last time.

“Wow,” said Tom Jentz, one of the city officials who had helped spearhead the effort to remove the railroad from downtown Kalispell.

The final crew to bring a train into downtown Kalispell, Montana. From left to right, engineer Kent Ainsworth, conductor Jake Thain, conductor Sam Pederson, general manager Kyle Jeschke, and office manager Pam Ridenour.

Epilogue

The first BNSF Railway train on the Kalispell Branch passes the Mission Mountain’s locomotive on April 1, 2020.

A few months after the final run into downtown Kalispell, BNSF Railway announced that it would be resuming service on the line between Columbia Falls and Kalispell. In a statement to the Flathead Beacon, BNSF officials said, “We are always looking to further serve customers as they expand their businesses, and this gives us that ability to do so.” BNSF’s decision to not renew Watco’s lease on the line meant that Mission Mountain would only operate the rail line between Stryker and Eureka, about an hour north of the Kalispell line. A number of Watco employees had to relocate or leave railroading because of the change.

Today, the Mission Mountain Railroad runs on a stretch of track between Eureka and Stryker, Montana. Most of the employees who worked for the railroad when it went to Kalispell have gone elsewhere.

Meanwhile, work continued in the downtown area to prepare for the construction of the new trail and other commercial development. In late 2020, much of the former CHS Kalispell grain elevator was torn down, however the original concert silos were preserved and plans are currently in place to use those as part of a new commercial development. An artist was also hired to paint a mural on top of the elevator in a nod to the area’s industrial history.

The Kalispell rail yard in late 2020.

The City of Kalispell also acquired a locomotive that will be put on display along the rail trail. The GP9 locomotive was cosmetically restored by Western Rail near Spokane, Washington, in a deal orchestrated by Derrick Klarr of Klarr Locomotive Industries. The locomotive arrived in Kalispell in November painted in the Great Northern Railway’s historic “Big Sky Blue” paint scheme.

Great Northern GP9 657 being delivered to Kalispell in November 2020.

More than a century ago, railroads like the Great Northern were the information superhighways of their day. With the arrival of a rail line, a town’s fortunes could change almost overnight. While this photo story has focused on Kalispell and the Flathead Valley, it’s a tale that can be told in nearly every corner of the American west, from Kalispell to Klamath Falls, Ely to Eastport.

As Kalispell looks toward its future, the right-of-way through it that was drawn some 130 years ago will help bring about a new era of prosperity while also reminding visitors that at one time, Kalispell was a railroad town…

Northwest Drywall spur before and after rail service ended in 2019.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Mission Mountain Railroad, CHS Kalispell, Northwest Drywall, City of Kalispell and the Flathead Beacon for their organizational support for this project. Special thanks to Kyle Jeschke, Pamela Mower, Tracy Smith, Jase Dean, Mark Lalum, Myron Swallow, Jason Sharp, Reed Edwards, Brent Keys, Dyllan Vincent, Bill Tripp, Kent Loveall, Jon Greiting, Kent Ainsworth, Jake Thain, Sam Pederson, Pam Ridenour, Derrick Klarr and any everyone else who let me point a camera at them during this project.

To read more about the final days of the railroad in Kalispell, see “End of the Line” in the September 8, 2018 edition of the Flathead Beacon. You can also watch a presentation I did about this project for the Center for Railroad Photography & Art on its YouTube page.

Story, photos and design by Justin Franz.

See more of my work at JustinFranz.com.